Home > TV

‘Makjang’: Escape into the absurd

|

| In a scene from “Everybody, Kimchi,” Lim Dong-joon (Won Ki-joon) is slapped in the face with kimchi. (MBC) |

A vindictive mother-in-law slaps the male lead with a thick wedge of kimchi. Neon green laser beams shoot out of a businessman’s eyes. A woman fakes her own death, gets plastic surgery and remarries her ex-husband to take revenge.

These are scenarios that have actually aired on prime-time Korean television series, and moreover been met with favorable ratings.

Locally, these types of shows are referred to as “makjang” -- vernacular for situations that seem too outrageous to be true. The genre is characterized by melodrama, violent emotional outbursts and absurd coincidence, alongside adultery, incest and sudden memory loss.

According to culture critic Jung Deok-hyeon, dysfunctional family relationships are at the center of makjang Korean drama series.

“The family story is a format that is familiar to everyone,” said Jung. “(The shows) tend to blow up the negative aspects of Korea’s traditional family structure, with oppressive father figures, conflicts between wives and mothers-in-law and discrimination among family members.

“Add violence and revenge and drama to that, and it makes for a sensational plot and characters that really push your buttons. It provokes a strong emotional reaction.”

While viewers generally denounce this genre as lacking any kind of logic or sophistication, many of Korea’s most notorious makjang series have achieved decent ratings and all have made headlines. The 2014 series “Jang Bo-ri is Here!” centering on the fierce competition between two daughters-in-law, for example, peaked at a strong 37.3 percent viewership, according to Nielsen Korea.

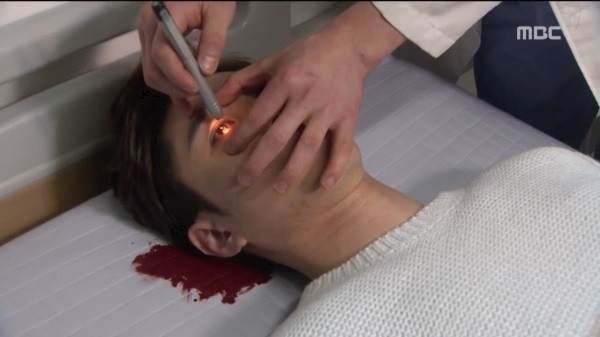

|

| Jo Nathan, played by actor Kim Min-soo, suddenly dies of a concussion after being pushed into a wall in “Apgujeong Midnight Sun.” (MBC) |

Series like “Princess Aurora,” which killed off 12 supporting characters and “Apgujeong Midnight Sun,” which received a warning from the Korea Communications Standards Commission for excessive violence, were the buzz of the day.

Avid television viewer Choi Han-yool, 27, says she enjoys the mindless escapism that the absurd yet easy-to-follow plotlines offer.

“You can just turn it on and immediately understand what’s happening,” she said. “There’s no need for any context. It’s simple who the villain is.”

Black-and-white morality is another main ingredient in makjang series.

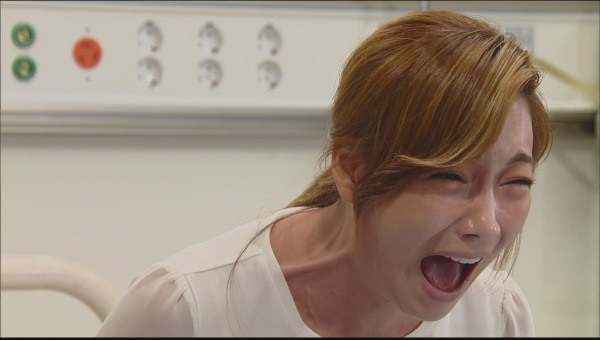

|

| A scene from “Jang Bo-ri is Here!” shows villainess Yeon Min-jeong (Lee Yoo-ri) wailing with anger. Amplified emotional outbursts are staples of Korean “makjang” series. (MBC) |

“Jang Bo-ri is Here!” features villainess Yeon Min-jeong, played by actress Lee Yoo-ri, who abandons her daughter, manipulates people and screams in corridors to get what she wants, eventually dumping her husband after he loses his wealth, among other outrageous acts.

“It’s fun to talk about what crazy things these characters will do next,” said Choi. “It’s like gossiping about someone without having to feel guilty.”

In the series, main character Jang Bo-ri is a girl who has struggled in life but has a heart of gold, a clear foil to Min-jeong.

Park Myeong-jin, professor of Korean literature at Chung-Ang University, says this clean-cut morality offers respite in a society ridden with uncertainty, which is why makjang series still score big with audiences.

“In the late 1990s, Korea was hit with IMF,” said Park, referring to the 1997 Asian financial crisis in which Korea was bailed out by the International Monetary Fund. “People lost jobs. The future became unclear for many, for no clear reason and through no fault of their own.”

And when things don’t unfurl according to a comprehensible, cause-and-effect sequence, people take refuge in the irrational and the violent, Park said.

“Reasonable plotlines cannot appeal to people living in a world that doesn’t follow reason,” he said.

Park additionally argues that in makjang series, no matter how unhinged the character or plot may become, the denouement always returns to traditional values. In “Bo-ri,” for example, the heroine, who represents utter goodness, lives happily ever after in the end, while the thoroughly evil Min-jeong is rightfully punished for her crimes. The family is salvaged; balance and peace are restored.

“People feel that things aren’t rightly compensated in their real lives, which is why they like seeing a simple version of justice win in TV shows.”

By Rumy Doo (doo@heraldcorp.com)